Introduction

This multi-part blog series will be discussing an undocumented feature of Windows: instrumentation callbacks (ICs).

If you have not yet read the first part of this series, we strongly recommend you read it to find out what ICs are and how to set them.

In this blog post you will learn how to do patchless hooking using ICs without registering or executing any user mode exception handlers.

Disclaimer

- This series is aimed towards readers familiar with x86_64 assembly, computer concepts such as the stack and Windows internals. Not every term will be explained in this series.

- This series is aimed at x64 programs on the Windows versions 10 and 11. Neither older windows versions nor WoW64 processes will be discussed.

Recap

In the first blog post we learned how to install an IC on a process and how to use that callback to interact with specific syscalls. We learned this by intercepting the syscall made by OpenProcess inside the subfunction NtOpenProcess. After intercepting NtOpenProcess, we close the handle that was opened and spoof a return value of STATUS_ACCESS_DENIED. This allows us to get a callback on every syscall that returns and which was made. However, it does not allow hooking arbitrary code. Also consider this: a program calls NtSetInformationProcess to set its own IC after you have already set an IC. Which IC do you think is called? Your original IC or the new IC passed in NtSetInformationProcess? Give it a try.

Hooking

If you are reading this article, there’s a good chance you know what patchless hooking is. If you don’t, we will explain the patchless part; however, you are assumed to know what hooking in general refers to.

There are many hooking techniques, but they are either patchless or require a patch. Regular inline hooks work by patching the executable memory/the binary to redirect execution to the code of the installed hook. Assuming a person wants to hook a binary file on disk, and changes (aka patches) the binary’s bytes, the signature of the binary is changed, as the binary no longer contains the same bytes.

Patchless hooking

As you might’ve guessed, patchless hooking techniques are techniques that do not require a patch. This means, none of the bytes in the executable memory region that is to be hooked are changed, so the signature of that memory region stays the same, meaning the hook can’t be detected by signature scans.

The most common patchless hooking techniques in Windows user mode are probably vectored exception handler (VEH) hooking and page guard hooking. Both these techniques utilize a core concept of Windows and operating systems in general: exceptions.

Page guard hooking works by setting the PAGE_GUARD memory page protection modifier on a certain memory page. Once that memory page is accessed, the system raises an exception that can be handled by an exception handler.

VEH hooking also requires setting up an exception handler, but instead of page guards, hardware breakpoints are used to trigger the exceptions.

Assuming you, for example, add a __debugbreak() to your C/C++ code that adds a software breakpoint, hardware breakpoints are generated by the CPU.

Hardware breakpoints can be set with specific registers in x86_64 CPUs:

- Dr0-3: These four registers contain the addresses of where the breakpoint should be set.

- Dr6: This is the status register that contains information about which breakpoint fired during exception handling.

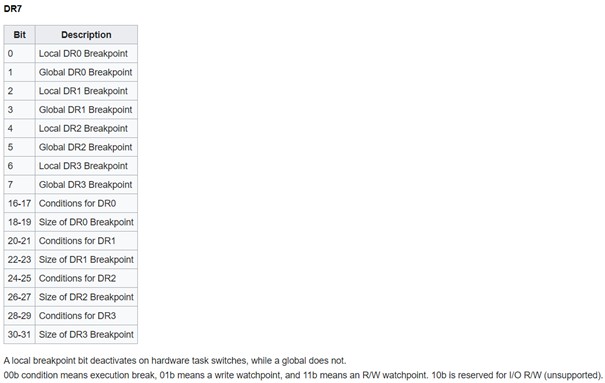

- Dr7: This is the control register that, using bit flags, controls which debug registers are active and what type of breakpoint is used: read/write/execute.

Exceptions and vectored exception handling

In short, VEHs allow developers to register their own exception handler. For this, Microsoft provides the function AddVectoredExceptionHandler. Let’s look at the function definition:

PVOID AddVectoredExceptionHandler(

ULONG First,

PVECTORED_EXCEPTION_HANDLER Handler

); |

The function takes a pointer to an exception handler function and an ULONG parameter. Internally, Windows stores the pointers to all the exception handlers in a linked list. If the ULONG parameter, i.e. the parameter called First, is not zero, the exception handler will be added to the start of the linked list instead of the end.

The Handler parameter takes a function pointer to the exception handler that should be added. The function should look as follows according to MSDN:

LONG PvectoredExceptionHandler(

[in] _EXCEPTION_POINTERS *ExceptionInfo

) |

The function should take a pointer to an EXCEPTION_POINTERS structure as that will hold the information about the exception which occurred. Most importantly, it will hold a CONTEXT structure of when the exception occurred. The CONTEXT structure holds processor-specific register data such as the member Rip containing the value the CPU register rip had when the exception occurred.

According to documentation, the exception handler should either return EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION (-1) or EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_SEARCH (0). This is used by Windows to decide whether the exception was handled or if the executed exception handler could not/did not want to handle the exception.

The process goes as follows: when an exception is thrown, a context switch to kernel mode occurs, which will then fill out an EXCEPTION_POINTERS structure based on the thrown exception. The kernel then returns to user mode and executes one VEH after another until one of them responds with EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION. If no VEHs to execute are left and the exception wasn’t handled, the process terminates.

The exception handling works based on a first-come, first-served principle: if a VEH in the linked list responds with EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION, the VEHs contained in the linked list after the executed VEH will no longer be executed.

There are ways to avoid calling AddVectoredExceptionHandler to register a VEH, for example by manually locating and manipulating said linked list. However, the same problems and IoCs remain:

- Our own VEH needs to be part of the linked list.

- All VEHs before our own VEH in the linked list are executed and can handle the exception first.

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could handle exceptions without adding our exception handler to the linked list while also guaranteeing that our exception handler is executed before any other exception handlers? Or without even calling the other exception handlers at all?

If you were a careful reader of the first part of the series, you might’ve already concluded where this is going: if an exception is a user-mode-to-kernel context switch, which then returns to user mode, can we intercept the return to user mode with our IC?

How convenient that we also created a PoC to log syscall names in the first part. Why don’t we just try using that PoC to see if something shows up when an exception is thrown?

KiUserExceptionDispatch

When an exception is thrown, the KiUserExceptionDispatch function from ntdll is called. As the kernel returns here, we’re guessing that this function most likely calls the registered exception handlers somewhere down the road. Let’s check this theory by opening ntdll! KiUserExceptionDispatch in a decompiler. Luckily, figuring out what the function does is simple because of function names provided by Microsoft:

+0x00 void KiUserExceptionDispatch() __noreturn

+0x00 {

+0x00 int64_t Wow64PrepareForException_1 = Wow64PrepareForException;

+0x0b void arg_4f0;

+0x0b

+0x0b if (Wow64PrepareForException_1)

+0x1a Wow64PrepareForException_1(&arg_4f0, &__return_addr);

+0x1a

+0x29 char rax;

+0x29 int64_t r8;

+0x29 rax = RtlDispatchException(&arg_4f0, &__return_addr);

+0x30 int32_t rax_1;

+0x30

+0x30 if (!rax)

+0x30 {

+0x4b r8 = 0;

+0x4e rax_1 = NtRaiseException();

+0x30 }

+0x30 else

+0x37 rax_1 = RtlGuardRestoreContext(&__return_addr, nullptr);

+0x37

+0x55 RtlRaiseStatus(rax_1);

+0x55 /* no return */

+0x00 } |

We can ignore the Wow64 functions because we are only focussing on ICs in non-Wow64 processes as mentioned in the disclaimer.

The code after the Wow64 functions looks interesting; RtlDispatchException is called with two parameters. The parameter names were auto-generated by BinaryNinja.

If we look at the disassembly of the function, we can see that both parameters used for calling RtlDispatchException are taken from the stack. This is also why the second parameter was named as __return_addr by BinaryNinja, as the address is on top of the stack, which is normally the return address. Further down the decompiled snippet, we see a call to RtlGuardRestoreContext. This function does not have documentation on MSDN; however, RtlRestoreContext does. If we peek into RtlGuardRestoreContext with a disassembler/decompiler, we can see it’s just a wrapper around RtlRestoreContext with some sanity checks. Looking at the documentation, we can see that RtlRestoreContext takes a pointer to a CONTEXT structure and an optional second pointer to a _EXCEPTION_RECORD struct. So, the parameter named __return_addr by BinaryNinja is a pointer to the CONTEXT structure of the exception. Theoretically, this would already suffice to do some basic hooks, but let’s get access to the other member of the EXCEPTION_POINTERS structure: EXCEPTION_RECORD. If __return_addr is the CONTEXT structure, the first argument is the EXCEPTION_RECORD structure, as that is also retrieved from the stack that was set up by the kernel for the user mode exception handling. Let’s not overcomplicate things with further static analysis; instead, we can write a program that uses VEH and attach a debugger to it. For this, I’ll use the following program that registers a VEH and then performs a null pointer dereference to cause an exception:

#include "Windows.h"

long exception_handler(EXCEPTION_POINTERS* exception_info) {

return EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_SEARCH;

}

int main()

{

AddVectoredExceptionHandler(1, &exception_handler);

bool* test = nullptr;

*test = true;

return 0;

} |

Following the compilation, the program was opened in the debugger WinDbg.

First, breakpoints on both the exception handler and the call to RtlDispatchException inside the function KiUserExceptionDispatch were set, as RtlDispatchException takes the pointer to the CONTEXT structure and another parameter, which might be a pointer to the EXCEPTION_RECORD structure.

0:000> bp ntdll!KiUserExceptionDispatch+0x29

0:000> bp exception_handler |

After resuming execution, the breakpoint in KiUserExceptionDispatch is executed first as expected. After the breakpoint is triggered, we read out rcx and rdx, because according to the Windows x64 calling convention, these registers will hold the first and second function parameter.

Breakpoint 0 hit

ntdll!KiUserExceptionDispatch+0x29:

00007ffe`2f571439 e8d20efbff call ntdll!RtlDispatchException (00007ffe`2f522310)

0:000> r rcx

rcx=0000003d38affa30

0:000> r rdx

rdx=0000003d38aff540 |

Now, we need to cross-reference these values with the values of the EXCEPTION_POINTERS structure that is passed to the exception handler. This can easily be done with a handy feature of WinDbg: the display type command (dt).

0:000> g

Breakpoint 1 hit

veh_hooking_test!exception_handler:

00007ff7`30c41000 50 push rax

0:000> dt EXCEPTION_POINTERS @rcx

veh_hooking_test!EXCEPTION_POINTERS

+0x000 ExceptionRecord : 0x0000003d`38affa30 _EXCEPTION_RECORD

+0x008 ContextRecord : 0x0000003d`38aff540 _CONTEXT |

As you can see, our assumption was correct: the parameters passed to RtlDispatchException are the EXCEPTION_RECORD and CONTEXT structure. As you can also see, KiUserExceptionDispatch calls RtlGuardRestoreContext on the CONTEXT structure after RtlDispatchException was executed.

RtlRestoreContext, the function internally called by RtlGuardRestoreContext, sets the registers of the specified thread as specified in the CONTEXT struct passed to that function. This means, rip, the instruction pointer, is also overwritten so code after the call to RtlRestoreContext is never executed. This also means that the C++ function (named instrumentation_callback in the previous blog post) won’t return to your assembly bridge to execute everything after the C++ function call. The IC flag will thus never be reset.

IC exception handling

We now know how we can get access to the EXCEPTION_RECORD and CONTEXT structures and know how KiUserExceptionDispatch resumes execution – with RtlGuardRestoreContext.

All we now need to do is get our IC to intercept KiUserExceptionDispatch, retrieve the EXCEPTION_RECORD and CONTEXT off the stack and resume execution if we want to handle the exception.

We will reuse the same assembly bridge as in the first part of this blog series.

For now, let’s not add hooking but instead create a regular exception handler that continues execution after an access violation. For this, a modified version of the code snippet previously used for debugging will be used. The following snippet adds a regular exception handler that returns EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION, which means that the exception was handled, and that the execution of the program can continue:

#include "Windows.h"

#include "print"

long exception_handler(EXCEPTION_POINTERS* exception_info) {

exception_info->ContextRecord->Rip += 3;

return EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION;

}

int main()

{

AddVectoredExceptionHandler(1, &exception_handler);

bool* test = nullptr;

*test = true;

std::println("Access violation skipped");

return 0;

} |

You might wonder why we are adding a hardcoded value of 3 to the value of rip that is saved in the CONTEXT record. This is used to skip the access violation at the line *test = true, as it gets compiled to the bytes c60001, so 3 bytes that need to get skipped to prevent the exception from being triggered again once execution continues.

In non-test code you would not want to do this, as a different compiler or the same compiler with different settings could also produce other instructions to perform the same logic. Normally, you would want to use a disassembler such as Zydis to disassemble the instruction rip points to, to dynamically calculate the length of the instruction. We decided against this to keep the snippet code as minimal as possible.

Let’s now remove the AddVectoredExceptionHandler line and try to replace it with an IC.

First, register an IC using the same logic/code as in the first part of this series. In this part, we will only cover changes to the instrumentation_callback function, as the rest remains the same as in the first blog post.

The following IC can be used to execute the same exception handler that would’ve been called if you added it with AddVectoredExceptionHandler. The code for the function is simple; if you’ve understood the blog posts so far you shouldn’t have a problem understanding it. The only part that was not covered was the offset of 0x4f0 from rsp to get the EXCEPTION_RECORD*. This comes from KiUserExceptionDispatch. We only showed the decompiled version of the code, which of course does not contain the stack offsets. If you disassembled that function and looked at the function call to RtlDispatchException, you would see the 0x4f0 offset.

You might also notice that we are using KiUserExceptionDispatcher instead of KiUserExceptionDispatch with GetProcAddress. That is because the function is exported as KiUserExceptionDispatcher.

extern "C" uint64_t instrumentation_callback(uint64_t original_rsp, uint64_t return_addr, uint64_t return_val) {

static uint64_t user_exception_addr = 0;

if (!user_exception_addr) {

user_exception_addr = reinterpret_cast<uint64_t>(GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandle("ntdll.dll"), "KiUserExceptionDispatcher"));

}

if (return_addr != user_exception_addr)

return return_val;

EXCEPTION_POINTERS exception_pointers = {};

exception_pointers.ContextRecord = reinterpret_cast<CONTEXT*>(original_rsp);

exception_pointers.ExceptionRecord = reinterpret_cast<EXCEPTION_RECORD*>(original_rsp + 0x4f0);

auto exception_status = exception_handler(&exception_pointers);

if (exception_status == EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_SEARCH)

return return_val;

RtlRestoreContext(exception_pointers.ContextRecord, nullptr);

// This will never be reached if RtlRestoreContext executes successfully

return return_val;

} |

With this code, the Windows exception handlers are never executed if our own exception handler returns EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION, as the code restores the context before the regular exception handlers are even called.

Hooking with ICs

Skipping access violations is cool, but it’s not useful compared to what else we can do with an exception handler. So, let’s return to the main topic of this blog post: how to hook code with ICs. For this, we will create an imaginary scenario: we have an installed IC and want to hinder someone else from overwriting/removing our IC. This will only work within the same process context because ICs are process-local – a different process can overwrite the IC remotely if it has the necessary privilege (SeDebugPrivilege).

We’ve touched on hardware breakpoints and debug registers before, but we haven’t set any. We mentioned that hardware breakpoints are set via CPU registers – the debug registers. This means, they are thread-specific: they will only trigger from the specific thread for which they were set. To set the breakpoints for the entire process, the hardware breakpoints need to be set for all threads, and you also need to be careful of thread creations.

Setting hardware breakpoints

To use hardware breakpoints, we first need to set the debug registers accordingly.

For this purpose, we created a function with the following function definition:

bool set_hwbp(debug_register_t reg, void* hook_addr, bp_type_t type, uint8_t len)

The definitions for the two custom enums debug_register_t and bp_type_t look as follows:

enum class debug_register_t {

Dr0 = 0,

Dr1,

Dr2,

Dr3

};

enum class bp_type_t {

Execute = 0b00,

Write = 0b01,

ReadWrite = 0b11

}; |

These are not mandatory; however, we use them to make our intentions clearer instead of directly requiring numbers or bit literals to be passed. As mentioned before, there are four debug registers that can contain the address of a breakpoint. Each of these debug registers has separate options that can be set. This allows execution, read, and read and write breakpoints.

Now Dr7, the control register, needs to be set accordingly.

OSDev wiki has a table explaining the structure of Dr7: