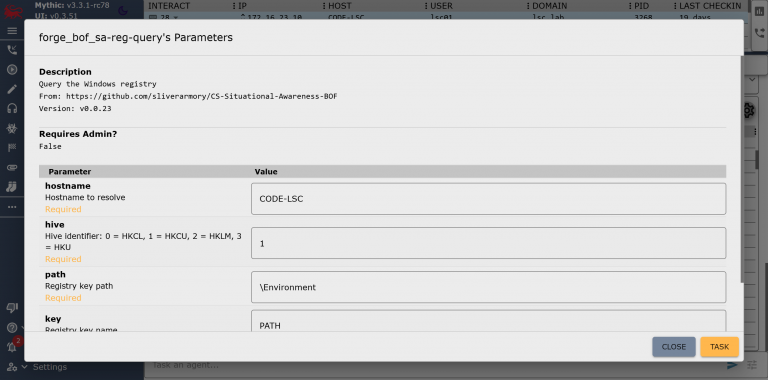

This is the third post in a series of blog posts on how we implemented support for Beacon Object Files (BOFs) into our own command and control (C2) beacon using the Mythic framework. In this final post, we will provide insights into the development of our BOF loader as implemented in our Mythic beacon. We will demonstrate how we used the experimental Mythic Forge to circumvent the dependency on Aggressor Script – a challenge that other C2 frameworks were unable to resolve this easily.

The blog post series accompanies the master’s thesis “Enhancing Command & Control Capabilities: Integrating Cobalt Strike’s Plugin System into a Mythic-based Beacon Developed at cirosec” by Leon Schmidt and the related source code release of our BOF loader.

Goals of our BOF runtime

As mentioned in the first part of this blog post series, several BOF loader implementations already exist. The best known is probably the COFF loader from TrustedSec (despite its name, the loader is fully able to run Cobalt Strike BOFs).

However, this loader was not usable for us for various reasons. Our own Mythic beacon has the peculiarity that it is built entirely as shellcode, which brought several disadvantages with it:

- The C standard library cannot be used (just like it is in BOFs and for the same reason: the linking step is missing in shellcode projects as well).

- The Windows APIs can only be accessed indirectly – a simple #include <Windows.h> and direct calls to the functions are not possible.

- Simple use of the process heap is not possible – memory always must be reserved and managed manually.

The COFF loader is based on all three of these features. Our task is therefore to build a loader that also complies with these restrictions. This will allow us to use it in our Mythic beacon. At the same time, we also increase compatibility with other projects in the offensive security field, which are often subject to the same restrictions. This means that we must observe the following:

- No functions from the C standard library may be used unless the compiler (in our case clang-cl) provides intrinsics for them.

- The use of Windows APIs should be kept to a minimum. If they are required for a specific task, they must be passed as function pointers by the caller of the loader. This means that the caller is responsible for determining how to resolve the functions.

- Memory management functions must also be passed by the caller. This allows the caller to define the memory management mechanics itself. The loader will not be able to function completely without memory allocations.

- The Beacon API functions should also be implemented and passed by the caller, as their implementation sometimes includes system-specific features. It cannot be verified that the caller supports these.

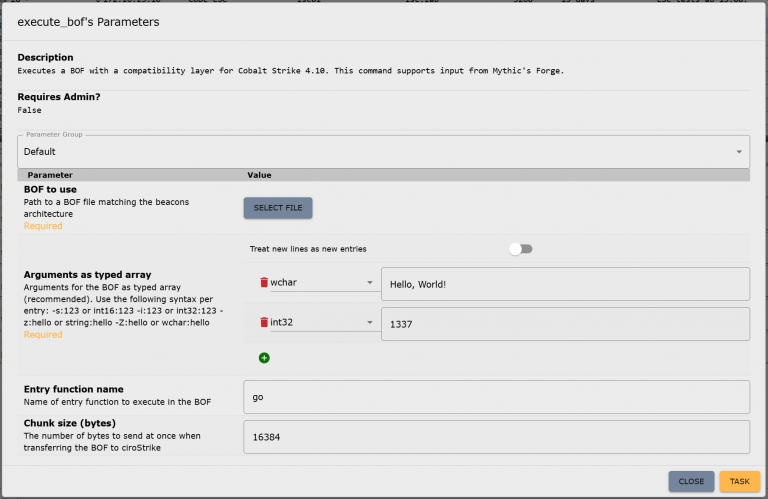

- The parameters for the BOF must be passed in the form of the size-prefixed binary blob, exactly as Cobalt Strike does. This ensures that the Data Parser API can correctly work with it. The binary blob must be created by the caller.

In the following sections, we describe how we achieved these goals. We have published our BOF loader at https://github.com/cirosec/bof-loader. It is therefore a good idea to look for the relevant code sections there to accompany this blog post. The included “TestMain” project implements the BOF loader exemplary, while the “BOFLoader” project includes, well, the BOF loader.

Implementation of our BOF loader

Preventing the usage of the standard library and Windows API

First, we need to get rid of some standard library calls and look for alternatives, especially those for string manipulation and memory management. memcpy and memset can be easily reimplemented manually (see BOFLoader/Memory.cpp). However, we need some help with allocation and deallocation: Here we use VirtualAlloc and HeapAlloc as well as VirtualFree and HeapFree from the Windows API. For HeapAlloc and HeapFree, we also need GetProcessHeap. These five functions can therefore be added to the list of functions that must be passed by the caller.

Regarding string manipulation, we can implement the functions strlen, strncmp, strncpy, strtok_r and strtol ourselves (see BOFLoader/StringManipulation.cpp). The string tokenizer strtok_r, which may be somewhat unusual in this list, is needed for the implementation of Dynamic Function Resolution (DFR) to split the string at the $ character (see the first blog post on this topic). The rest of the functions are needed from time to time, e.g., to process section or symbol names.

That almost checks off the first item from our requirements list. We still need the four Windows API functions that are linked to the BOF by default because our loader needs to know them too: LoadLibraryA, GetModuleHandleA, GetProcAddress and FreeLibrary. We’ll now define function types for all of these functions so that the caller knows which function signatures to comply with. We also want to leave it up to the caller to decide how DFR should resolve functions. To do this, we additionally define the function type ResolveFunc_t, which takes the library name and function name as parameters of type const char* and should return the function pointer as void*.

We call all these functions external functions, for which we define a struct that is used to hold the pointers to them. The definitions for them look like this:

#include "wintypes.h" // for Windows types (e.g. HANDLE, LPVOID, etc.)

typedef LPVOID(__stdcall* VirtualAlloc_t)(LPVOID lpAddress, SIZE_T dwSize, DWORD flAllocationType, DWORD flProtect);

typedef BOOL(__stdcall* VirtualFree_t)(LPVOID lpAddress, SIZE_T dwSize, DWORD dwFreeType);

typedef LPVOID(__stdcall* HeapAlloc_t)(HANDLE hHeap, DWORD wFlags, SIZE_T dwBytes);

typedef BOOL(__stdcall* HeapFree_t)(HANDLE hHeap, DWORD dwFlags, LPVOID lpMem);

typedef HANDLE(__stdcall* GetProcessHeap_t)();

// These functions are the ones that are injected to a BOF by default

typedef HMODULE(*LoadLibraryA_t)(LPCSTR lpLibFilename);

typedef HMODULE(*GetModuleHandleA_t)(LPCSTR lpModuleName);

typedef FARPROC(*GetProcAddress_t)(HMODULE hModule, LPCSTR lpProcName);

typedef BOOL(*FreeLibrary_t)(HMODULE hLibModule);

// DFR resolve function

typedef void*(*ResolveFunc_t)(const char* lib, const char* func);

typedef struct external_functions {

VirtualAlloc_t VirtualAlloc;

VirtualFree_t VirtualFree;

HeapAlloc_t HeapAlloc;

HeapFree_t HeapFree;

GetProcessHeap_t GetProcessHeap;

LoadLibraryA_t LoadLibraryA;

GetModuleHandleA_t GetModuleHandleA;

GetProcAddress_t GetProcAddress;

FreeLibrary_t FreeLibrary;

ResolveFunc_t ResolveFunc;

} external_functions_t, * external_functions_ptr_t;