What are Beacon Object Files and why do we need them?

Beacon Object Files, or BOFs for short, are compiled programs written to a convention that allows them to execute within the Cobalt Strike beacon process. They are a way to rapidly extend the beacon’s functionality with new post-exploitation features written in pure C code. It allows the beacon to be modified and extended after deployment since native features would need to be implemented beforehand. This would also result in a bigger size on disk, which may impede EDR evasion or the use of specific shellcode invocation techniques, such as the exploitation of Microsoft Warbird, which we have previously covered in another blog post. Native features can even be replaced by BOFs, which can further reduce the size on disk.

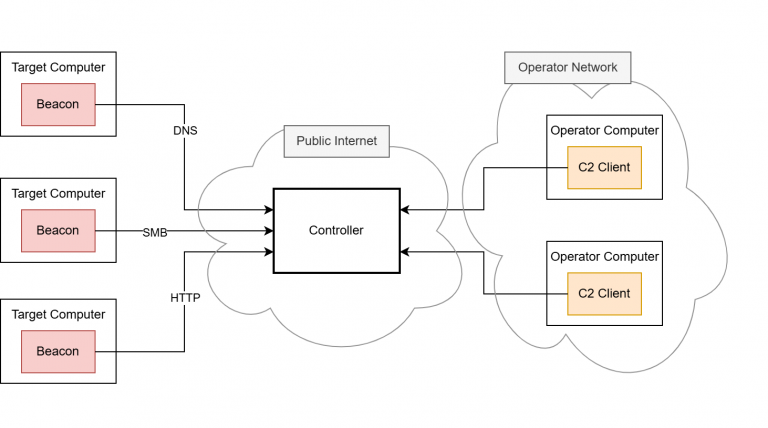

Running code within the beacon process, however, is nothing new in the C2 world. Many frameworks already offer the execution of PowerShell scripts, native PE files and .NET executables. The underlying techniques are usually less sophisticated, as they rely on existing functions of the Windows operating system – particularly the PE loader, the Common Language Runtime (CLR) for .NET executables or the PowerShell runtime. When launching executable programs, the operating system must provide a runtime in a separate process. This is known as “fork and run” and describes the creation of an auxiliary process as a child process (“fork”), in the context of which the program to be loaded is then executed (“run”). The creation of processes and threads is usually closely monitored and regulated by EDR software, which is why fork and run has not been a viable solution in well-secured environments for some time now. .NET executables also run through the Antimalware Scan Interface (AMSI), and removing it is often detected. EDR software is developing rapidly in this area.

This is exactly where BOFs come into play. They are designed in such a way that they are not dependent on the fork-and-run pattern but instead can be executed completely within the beacon process. Of course, this also has the advantage that they do not have to be stored on the hard disk at any time. Since BOFs are developed in C, they theoretically are unlimited in their range of functions.

Due to the relatively high popularity of BOFs (at least within the Cobalt Strike environment), there are already many implementations of known attacks that we also want to make use of. We will see some of them in the second part of this blog series.

While Cobalt Strike, as the pioneer project using BOFs, has a whole ecosystem built around them, Mythic lacks native BOF support. Porting them to other frameworks has been done several times: Havoc, Sliver, Empire and Brute Ratel are other C2 frameworks that also support BOF execution. However, many of these solutions lack compatibility with BOFs that were explicitly built for Cobalt Strike. This is often because many BOFs are instrumented by Cobalt Strike’s Aggressor Script – a proprietary scripting language that manages the invocation of BOFs on the server side amongst many other things. Aggressor Script is based on Sleep, an interpreter language for the Java Virtual Machine (JVM), which is why it cannot be used for Mythic (or any other C2 framework not written in Java).

Likewise, the implemented loaders are technically dependent on the C2 infrastructure in some cases, making it difficult to port them to Mythic. Our goal was to avoid these issues with our own approach and thereby make BOFs usable for us as well. The third part of this blog series covers the development of our BOF loader in detail as well as how we bypassed the dependency on Aggressor Script. But first, we will look at the BOFs’ file format to see how they work.

How do BOFs work?

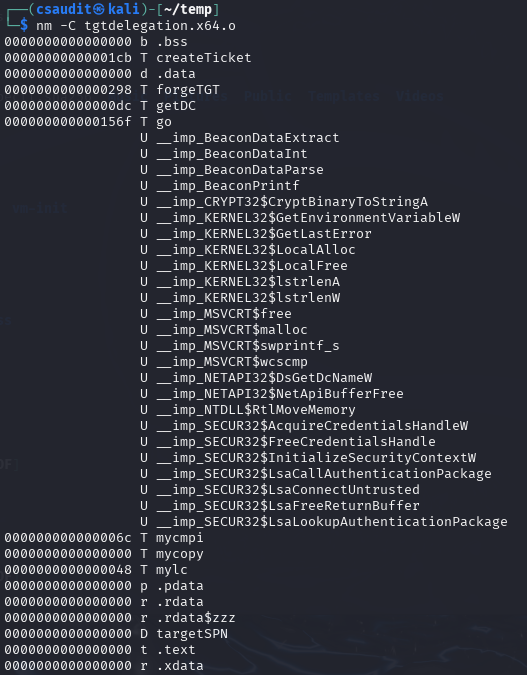

Forta’s official documentation on developing BOFs is our first point of reference for explaining how they work. It shows the minimum code boilerplate for a BOF and compiler calls for it.

#include <windows.h>

#include "beacon.h"

void go(char *args, int alen) {

BeaconOutput(CALLBACK_OUTPUT, "Hello, World! ", 13);

}

We will go into detail about the sample code later. Let’s just assume that this is working BOF code that outputs “Hello, World!”.

Since BOFs are designed to run on Windows, they should be compiled with a Windows-native compiler or the cross-compiler toolchain MinGW if you want to build on Linux. These sample calls are listed in the documentation:

- cl.exe /c /GS- hello.c /Fo hello.x64.o

for compilation on Windows - x86_64-w64-mingw32-gcc -c hello.c -o hello.x64.o

for compilation on Linux using MinGW

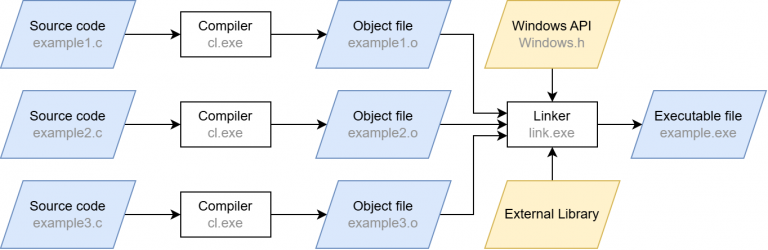

These calls will compile the source code input file hello.c, which includes our boilerplate BOF code. You may have noticed the /c and -c switches. Apart from those flags, these are just standard compiler calls (the /GS- flag for cl.exe simply disables the stack overflow protection). The /c and -c switches stand for “compile only”, which may sound redundant at first – after all, we are working with a compiler. However, a usual compiler call does more than that: after compilation, the linker is automatically invoked. The compilation step merely converts the source code into machine code. The linker then ensures that external functions are resolved (“linked”) and that the machine code is converted into the executable Portable Executable (PE) format.

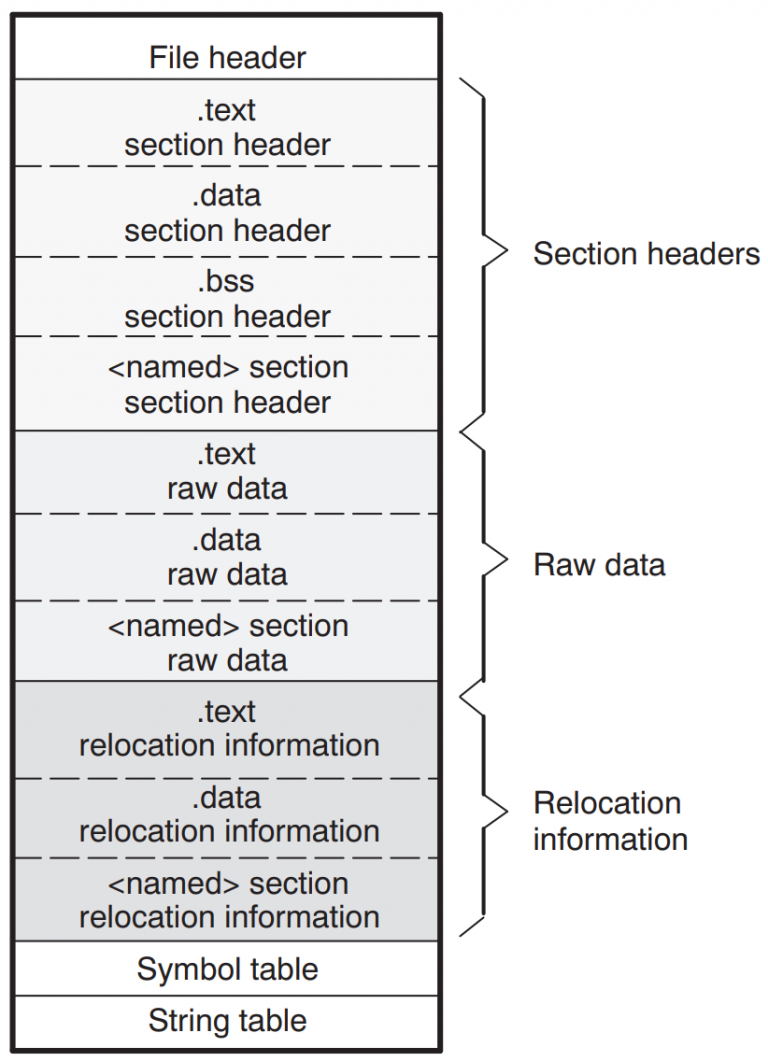

When the linking step is left out, the compiler produces a so-called object file (ending in .o or .obj) from the source code instead of a runnable program. Although this file contains the translated machine code, it does not yet contain a complete execution environment. In particular, there are no references to external libraries and functions: their pointers are not yet filled with actual addresses, which is one of the tasks the linker would do. Skipping the linker also has the effect that there can always be exactly one object file per translation unit, which is just the fancy term for a single C/C++ source code file after precompilation. Linking several object files together is also a task of the linker. It also provides the entry point for the executable so that the operating system knows where to begin running it.

A simplified compilation process is shown below. In our case, we stop after the compilation step and are thus left with the .o files.