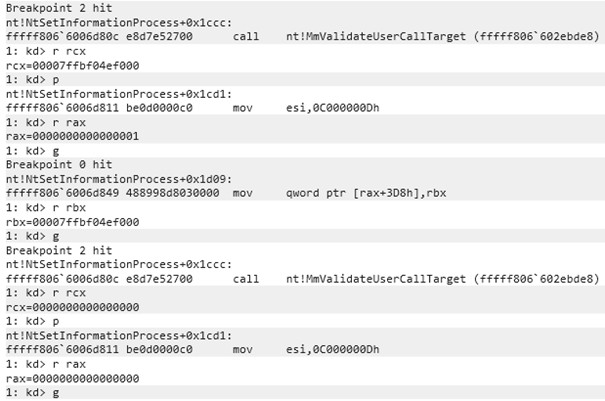

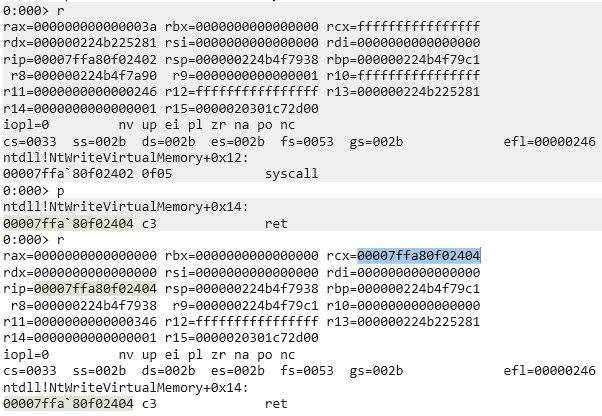

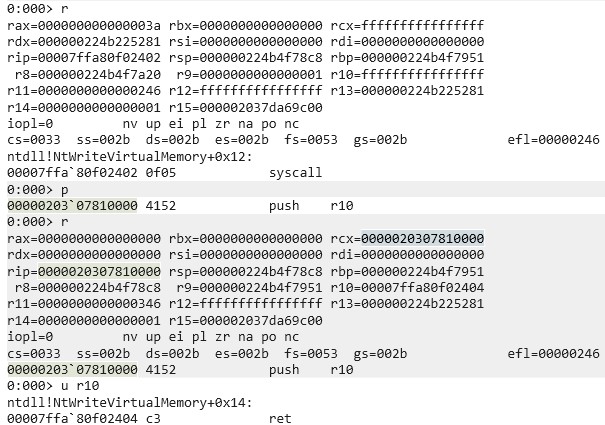

As expected, r10 contains the address of the actual return address. The picture also shows that rcx contains the address of the start of the IC instead of the actual return address.

This means, we can detect poorly written ICs by checking rcx and r10 at the ret instruction after the syscall, that is the instruction it would normally execute if no IC was set. These registers can of course be arbitrarily changed by the IC, but that needs to be kept in mind by the author. If rcx isn’t properly set, it does not only leak that an IC is set but also where it is located in memory, which could be used to automatically dump it or for something even more interesting ‑ which we will get to.

Preventing ICs from getting set

If it is hard to detect whether an IC is set or not, we could try preventing others from setting them in the first place. This is not very easy to do. Let’s assume two different starting points of an attacker: the attacker is inside the process on which he wants to set an IC or the attacker is in another process. If the attacker is already in the kernel, you got entirely different problems so we will not discuss that.

One’s own process context

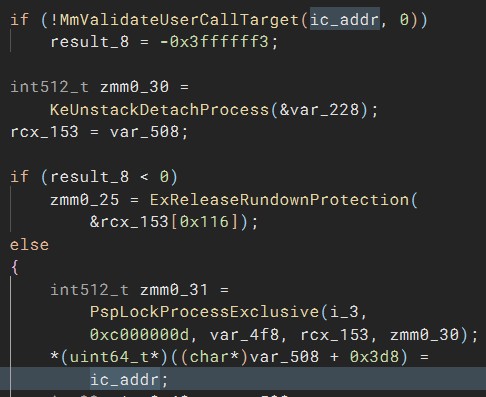

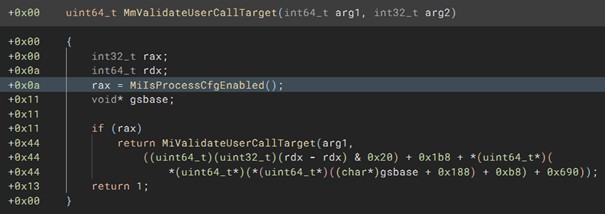

In the second part of this blog post, we already discussed one way of preventing the IC from getting overwritten, which was done by hooking NtSetInformationProcess. For a simple attacker this suffices; however, the hook can be avoided through direct and indirect syscalls. Even if the syscall instruction in NtSetInformationProcess is hooked, an attacker could use the syscall instruction of another Windows API to not run into the hook. This would mess up the callstack, but to detect that, a kernel driver would be required as once the syscall was executed and returned to user mode, the new IC is already set. Another idea is to place a page guard on the memory page of NtSetInformationProcess after registering an appropriate exception handler to detect SSN reads of the SSN of NtSetInformationProcess or nearby syscalls; this would however take a toll on performance.

Another detection mechanism is using a heartbeat. The originally set IC could use a counter that increments on every IC execution, while some regular code that is not in the IC checks every few seconds if the counter was incremented. If the counter wasn’t incremented in a while, the IC was overwritten, as syscalls are, depending on the program, constantly made. This way the program could then try reregistering its own IC, which is not guaranteed to succeed, but the program can again detect through the counter if reregistering the IC was successful.

If the attacker’s IC is adjusted to the program, he could of course also increment that counter himself, or even more interesting: if the previous ICs address was leaked through the beforementioned ways, the attacker’s IC could call the previous IC through its own IC while filtering what is passed to it. This means, it is not only interesting for attackers to hide that an IC is set but also for defenders as there’s no proper way of being entirely sure that your IC is the registered one. At this point we are talking about a very sophisticated attacker, as the IC would need to be highly adapted. If the victim process does not repeatedly dump the IC address itself (very unlikely), it has no way of knowing if its own IC was overwritten, as any detection logic in that IC can be automatically executed by calling the IC from the new, actually set IC.

Other process context

As initially mentioned, setting an IC on another process requires the SeDebugPrivilege. This is a very extensive privilege. If the user does not have this privilege, there is no way for him to set an IC on another process. This means, properly hardening your environment and stripping users of unneeded privileges is also the best defense against ICs being set on other processes.

Let’s assume the user has the SeDebugPrivilege. In that case the victim process can’t do much against an IC being set other than repeatedly scanning for open handles and closing those with the PROCESS_SET_INFORMATION access mask. This contains a race condition, as with the correct timing an IC can still be set. Of course, once the IC is set the same detection mechanisms mentioned in “One’s own process context” apply again.

Closing words

This marks the end of this blog series. Congratulations if you read through all of it! If you got questions or built upon this research (as there’s still a lot to discover with ICs), feel free to reach out.